The Day Sierra Leone Executed Its Own Vice President.

The saying that “what goes around comes around” found one of its darkest meanings in the life and death of Francis Misheck Minah, Sierra Leone’s former Vice President. Once among the most powerful men in the country, he was executed in 1989, the same way others had fallen before him, under laws he had once defended.

How it all started:

In the late 1980s, Sierra Leone was a nation trapped between power and fear. The dreams of independence had long faded, replaced by corruption, economic collapse, and quiet struggles among the men who once stood together at the heart of government.

Among them was Francis Misheck Minah, one of the most gifted and controversial figures in Sierra Leone’s modern history. Born in Sawula, Pujehun District, in the south of the country, Minah rose from a humble background to become one of the brightest legal minds of his generation. He studied law in Britain before returning home to serve under President Siaka Probyn Stevens, the founding leader of the All People’s Congress (APC).

From the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, Minah’s rise was steady and impressive. He held some of the most powerful offices in the land, Minister of Foreign Affairs (1975–1977), Attorney General and Minister of Justice (1977–1979 and again in 1984–1985), Minister of Finance (1978–1981), and finally, Vice President (1985–1987) under President Joseph Saidu Momoh, who succeeded Stevens.

By the mid-1980s, Minah had become one of the most influential men in the ruling APC, a key power-broker in a one-party state, where loyalty mattered more than truth. Yet, his growing influence also made him a target.

Tensions soon developed between Vice President Francis Minah and James Bambay Kamara, the powerful Inspector General of Police. The two men had once worked closely but later fell out bitterly over issues of loyalty, power, and control. Their rivalry added to the quiet unease already spreading through the government.

At the same time, Abdulai Conteh, the Attorney General and Minister of Justice, emerged as another key figure in the political equation. Conteh’s growing closeness to President Momoh and his control of state prosecutions placed him at odds with Minah’s circle of influence. Rumours swirled that factions were forming at the highest levels, one behind Minah, the other behind Conteh and Bambay Kamara.

Then came March 1987.

Security forces announced that they had discovered a cache of weapons and ammunition in a house in Freetown. The discovery, which included rocket launchers, rifles, and military uniforms, was immediately linked to an alleged plot to overthrow President Momoh’s government.

Within hours, the country was gripped by fear and suspicion. Soon, the name of Francis Misheck Minah, the sitting Vice President, appeared on the list of those accused of plotting the coup. The news stunned the nation. To many Sierra Leoneans, it seemed impossible that a man who had served every government since Siaka Stevens would turn against the state. To others, it looked like a political purge, a carefully staged attempt to remove a powerful rival.

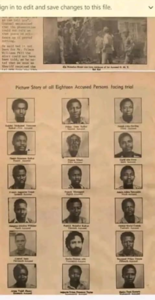

Alongside Minah, several other prominent figures were arrested, Gabriel Mohamed Tennyson Kaikai, a senior police officer; Jamil Sahid Mohamed Khalil, a Lebanese–Sierra Leonean businessman; and a number of civil servants and security officers. Together, they became known as the “Minah and Others” in what would later be remembered as one of Sierra Leone’s most controversial trials.

The trial opened in 1988 under the full glare of public attention. The prosecution, led by Attorney General Abdulai Conteh, argued that Minah and his co-accused planned to topple the government using the discovered weapons. The trial divided the country even more. Abdulai Conteh, as Attorney General, led the prosecution against Minah, his former cabinet colleague. The evidence was circumstantial, based largely on testimonies that many described as inconsistent and coerced. But in a climate where loyalty meant survival, few dared to question the process openly.

The defence maintained that the evidence was fabricated, planted by political enemies who feared Minah’s growing popularity and influence.

Inside the courtroom, the atmosphere was tense and unpredictable. Witnesses were questioned under pressure, and reports circulated that some had been intimidated. Outside, ordinary citizens watched in disbelief as the case unfolded, unsure whether they were witnessing justice or politics in disguise.

By the time the verdict was read, the outcome felt almost inevitable. The court found Francis Misheck Minah and seventeen others guilty of treason. President Momoh approved the sentence. Appeals for clemency from religious and civic leaders were ignored.

What made Minah’s downfall even more haunting was the shadow of his own past. In 1975, when Dr Mohamed Sorie Forna, Ibrahim Bash-Taqi, and thirteen others were executed for an alleged coup, Minah was Sierra Leone’s Attorney General and Minister of Justice. He had stood firmly with President Siaka Stevens and advised against granting clemency, even as religious leaders and civil society pleaded for mercy. The law, he argued then, must take its course.

Fourteen years later, that same law consumed him.

On October 7th, 1988, the Vice President of Sierra Leone, a man who had served as Attorney General, Minister of Finance, and Foreign Minister, was hanged at Pademba Road Prison. Several of his co-accused were executed alongside him.

The execution of Francis Minah sent shockwaves across Sierra Leone and beyond. In Pujehun District, people wept for their fallen son. In Freetown, fear deepened, and whispers filled the air, whispers that the case had been more about politics than treason.

The government of Joseph Saidu Momoh would never recover its credibility. Many within the ruling APC began to lose faith, and divisions widened between the military, the police, and the civilian elite. Sierra Leone’s economy continued to crumble. By the early 1990s, the country was sliding into the chaos that would soon become the civil war.

History has not been kind to the memory of Francis Minah, nor has it been clear. Some saw him as a victim of political conspiracy, others as a man who flew too close to power and fell to its flames. What remains certain is that his death marked the end of an era, the last execution of a sitting Vice President in Sierra Leone’s history.

That morning in October 1989, Sierra Leone did not only execute a man. It executed another piece of its conscience.

And even today, one question remains unanswered:

Was Francis Minah truly guilty, or was he silenced by the same system he helped to build?

Follow The Sierra Leone Story for the next chapter, how power, betrayal, and silence led Sierra Leone into the fires of the 1990s civil war.