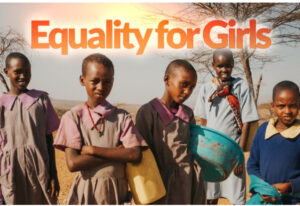

The Hidden Struggles and Triumphs of Girls’ Education

By Mackie M. Jalloh

In the sun-drenched savannahs of northern Sierra Leone, under the thatched shade of a rural community center, a quiet revolution is unfolding. It is not waged with protests or politics, but with pens, courage, and resilience. Here, amidst economic fragility and generations of cultural traditions, girls once denied the right to dream are reclaiming their voices through education. Their journey, however, is neither linear nor guaranteed.

Across West Africa, the education of girls is caught in a complex web of tradition, poverty, conflict, and systemic neglect. Governments preach development. Donors pledge millions. Yet, millions of girls still wake each day unsure whether they’ll step into a classroom or carry buckets to fetch water. The path to school is not merely a matter of logistics—it is a negotiation with poverty, patriarchy, and personal trauma.

This story journeys deep into the heart of this crisis—not just with numbers and policy rhetoric, but with the lived experiences of girls defying the odds. It also challenges the conventional narratives, urging us to stop seeing education as merely access to school, but rather as empowerment, safety, voice, and liberation.

A Crisis Cloaked in Normalcy

In Kambia, a border district battered by poverty and post-conflict fatigue, 13-year-old Wullamatu lost both her parents and her right arm in an accident when she was eight. She now attends school with the support of the Accelerating Girls’ Empowerment (AGE) project, but every morning is a struggle. “People stare,” she says quietly. “But when I’m in class, I feel equal.”

Her story, though exceptional in its trauma, is not unique in its challenge. Across Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and parts of Nigeria, girls face an overwhelming set of obstacles just to sit at a desk. School is often distant. Fees and uniforms remain unaffordable. The threat of sexual harassment and gender-based violence looms both inside and outside classrooms.

In these regions, education policy is often reactive rather than proactive. Initiatives tend to surface in response to donor requirements or crises—Ebola, COVID-19, or international pressure—rather than as an entrenched national priority. As a result, girl education remains vulnerable to political instability, aid withdrawal, and cultural resistance.

Numbers That Mask Realities

According to the World Bank, more than 129 million girls globally are out of school. This includes 32 million of primary school age and 97 million of secondary age. But global figures, though staggering, mask regional nuances. In FCV (fragility, conflict, and violence) zones like northeastern Nigeria and parts of the Sahel, girls are 2.5 times more likely to be out of school than boys. And even when girls do enroll, fewer complete. In Sierra Leone, for example, only 63% of girls finish primary school, compared to 67% of boys.

What these statistics don’t capture are the psychological scars girls carry—the internalized belief that they are less worthy of education, the fear of ridicule during menstruation due to lack of sanitation, or the trauma of being forced into marriage before finishing school. In many communities, dropping out is not a decision—it’s a consequence.

When Classrooms Become War Zones

Education should be a safe space, but for many girls in West Africa, it isn’t. From unlit walkways to school toilets without doors, girls navigate daily threats. In some regions, even teachers pose a danger. Reports from Sierra Leone and Liberia point to systemic sexual exploitation by educators, often in exchange for grades.

Mariama, now 17, recounts her experience in Koinadugu. Pregnant at 15 and ostracized by peers and teachers, she was forced to leave school. “I felt invisible,” she says. “People looked at me like I had failed, not that I was failed by the system.”

With support from the “We Day Kam Back” project by CAUSE Canada, she is now back in school. But her trauma lingers, echoing the experiences of thousands of teenage mothers who are often denied reentry into formal education across the region.

Technology: A Bandage or a Bridge?

With the explosion of mobile technology and remote learning platforms, international agencies have touted e-learning as a silver bullet. But in many parts of West Africa, digital access remains a mirage. Girls in rural communities lack not just smartphones, but also electricity, internet, and digital literacy.

Still, there are glimmers of success. The Mobile Learning Lab model used in Sierra Leone’s rural north allows girls to access content offline via tablets. Local facilitators, often women from the same communities, guide the sessions. This human-centered approach has helped over 800 girls restart their education. Fatma, one of the beneficiaries, calls it her “second birth.” Orphaned and pulled out of school to work on a farm, she now dreams of becoming a doctor.

But the question remains: is technology truly inclusive, or does it deepen the digital divide when unaccompanied by infrastructure, mentorship, and community ownership?

Cultural Shackles: Breaking Traditions with Tact

Perhaps the most stubborn barrier to girl education in West Africa is culture. Deeply embedded gender roles, early marriage traditions, and taboos around menstruation often dictate a girl’s fate before she turns ten.

In many rural villages, girls are seen as economic liabilities. Marrying them off early is considered a financial relief. Even in urban centers, there remains a pervasive myth that “book learning spoils girls.” These beliefs are passed down by elders, reinforced by religious misinterpretations, and sometimes internalized by the girls themselves.

But change is happening. Community-based programs that engage religious leaders, parents, and local chiefs have proven successful in shifting mindsets. In Kailahun, a grassroots initiative known as “Fambul Tok” uses storytelling circles to unpack gender roles and rebuild consensus around girl education. Through dialogue, shame turns to understanding, and resistance becomes support.

Rethinking the Role of Government and Donors

Governments across West Africa often launch bold education strategies with media fanfare—free tuition policies, girls’ education funds, textbook subsidies. But implementation is fraught with bureaucracy, corruption, and lack of monitoring.

What’s missing is a gender-transformative approach that doesn’t just add girls to classrooms but rethinks what those classrooms mean. Are curricula inclusive? Are teachers trained in trauma-informed pedagogy? Are girls allowed to question, lead, and innovate?

Donors, too, must evolve. Rather than fund short-term, outcome-based projects, they should invest in capacity building, teacher training, and long-term mentorship models. Accountability should go beyond school attendance figures and reflect real empowerment.

The Power of Story: How Personal Narratives Are Driving Change

Policy papers don’t move hearts—stories do. Victoria, a 15-year-old orphan who re-entered school through CAUSE Canada’s intervention, now speaks at community events. “I was almost lost,” she says. “Now I speak for those still in the dark.”

In Makeni, 19-year-old Aminata runs a radio program focused on girls’ issues. Her broadcasts cover menstruation, consent, and education. “We must teach girls not just to read, but to speak,” she says. “And society must learn to listen.”

These stories are not outliers—they are templates. Empowerment begins when girls see themselves in narratives of strength, not pity.

Collective Responsibility: Beyond Schools and Governments

The future of girls’ education in West Africa does not lie solely in policy papers or foreign aid. It lies in collective accountability—from fathers who resist marrying off their daughters, to teachers who challenge stereotypes in their classrooms, to youth leaders who mentor younger girls.

Actionable steps are everywhere:

• Mentorship: Local women professionals mentoring schoolgirls create a ripple of confidence.

• Safe Spaces: Youth clubs and community learning centers offer psychological safety and peer support.

• Advocacy: Citizens must demand gender equity in budgets, school boards, and government decisions.

• Men as Allies: Gender equality is not a women’s issue—it is a human issue. Male champions, particularly local influencers, can be powerful advocates.

Looking Ahead: The Future We Must Forge

UNESCO’s data shows 50 million more girls have been enrolled in school since 2015. The G7 aims to reach 40 million more by 2030. But enrollment is not enough. We must move beyond access to education toward transformation through education.

The next decade must be one of integration—of trauma-informed teaching, digital inclusion, cultural engagement, and sustainable funding. Governments must not just promise, but deliver. Communities must not just support, but co-create.

This is not just about girls. It’s about reshaping West Africa’s social fabric. An educated girl becomes a woman who can lead, legislate, and liberate others. She uplifts families, inspires peers, and challenges systems. She is not a cost—she is a catalyst.

Final Word: A Call to Conscience

In a continent rich in history, culture, and potential, failing to educate half the population is not just a tragedy—it is sabotage. West Africa cannot speak of progress while girls remain silenced. We cannot build prosperity on the backs of children denied the right to learn.

To every policymaker, parent, donor, and citizen: girl education is not charity. It is justice. It is peace. It is development.

It is time we stopped asking why girls drop out—and start asking why we allow them to.

Let us rise—not with pity, but with purpose. Not with slogans, but with systems. Not with token gestures, but with transformative action.

Because when a girl learns, the future listens.